Mysterious Medieval Monuments at Fordham

by Dr. Madeleine Gray

Madeleine Gray PhD, FRHistS, FSA, FRSA is Professor Emerita of Ecclesiastical History/ Athro Emerita Hanes Eglwysig at the

Faculty of Creative Industries/ Cyfadran Diwydiannau Creadigol, University of South Wales/ Prifysgol De Cymru.

You can follow Dr. Gray on Twitter @heritagepilgrim and visit her blog at http://www.

When the Friends took over the church of St Mary, Fordham, just south of Downham Market in Norfolk, in 2011, it had been deconsecrated for a couple of decades and had lost most of its fittings. A few intriguing things remained: a medieval bell, a medieval pew with a lion carved on the end, and two medieval tombstones.

The tombstones are both on the altar steps, but they have clearly been moved there from somewhere else. They are placed on top of the tiles, and are lying north-south rather than east-west, the usual way of placing tombstones. And they have presented us with something of a puzzle! An inscription would have been helpful, but not many medieval memorials have inscriptions. It seems that the collective memory of the parish was expected to hold the identity of those who were important enough to have a memorial.

So who did these stones commemorate, and when did they die?

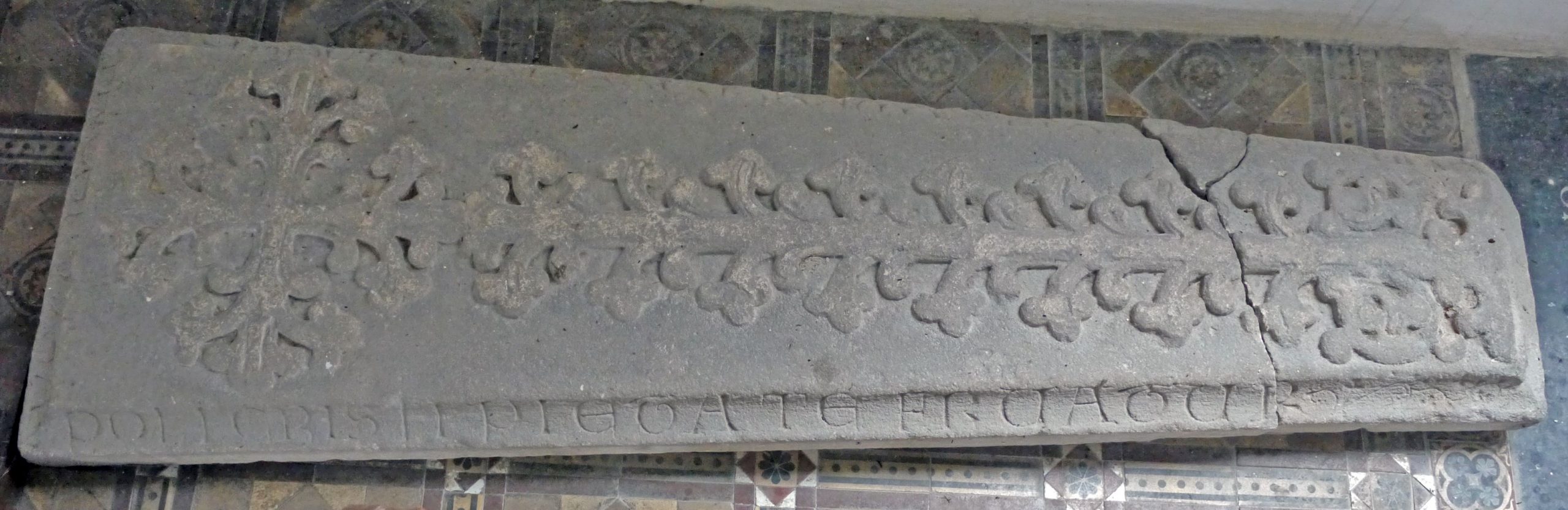

The larger of the two stones is beautifully decorated with an elaborately floriated cross. The shaft of the cross has branches with stylised foliage.

A similar stone can be seen at Hickling, Norfolk; that one bears an inscription in Lombardic lettering to a woman, Rosa.

(photograph of the Hickling memorial © Tim Sutton)

At the bottom of the Fordham stone, two little wyverns are biting the bottom of the shaft. The decoration looks early fourteenth century but the little wyverns are typical of late thirteenth century carving — so we can guess that the stone dates from about 1300.

And what is a wyvern, and why do you find them on tombstones?

A wyvern is a small dragon but with only two legs. You often find them carved on rood screens – there are good examples in the Friends’ churches at Derwen and Llangwm. But what do they symbolise? Usually, the dragon means something evil — so what are these little dragons doing in churches? Opinion is divided on this subject, and it may depend on context. The wyvern on the tomb probably reflects Psalm 21 verse 13: 'Thou shalt walk upon the asp and the basilisk: and thou shalt trample under foot the lion and the dragon'. It therefore shows the stem of the cross piercing a symbol of evil. Wyverns may also symbolise evil when they appear on rood screens. On the other hand, it has been suggested that the vine trails coming out of their mouths are the good news of Jesus, the True Vine. Were they evil, or good spirits? Like many medieval symbols, their intended meaning is now ambiguous.

The stone is wedge-shaped, with a decorated edge, and it has been described as a coffin lid. It is unlikely, though, that such an impressive piece of carving would have been seen once at the funeral and then buried. Earlier medieval coffins were often made of stone and just sunk into the floor of the church, with the lid still visible. This continued, less commonly, into the 15th century. However, by 1300 it was also possible for the deceased to be buried below the floor in a shaft, wooden coffin or simply a shroud, with a coffin 'lid' the only visible memorial, incorporated into the floor.

The smaller coped grave-slab is unusual in being decorated with a double-ended cross. It’s older than the floriated slab — circa 12th century. Similar designs can be seen on 11th-12th century grave slabs at Llantrisant and Bridgend in Wales.

Its small size may indicate a child’s burial, or it could be a heart or viscera/entrails monument. According to Sally Badham, who recently published a comprehensive study of these burials: ‘There were a number of reasons for divided burial, from the practical to the devout. First was the example of those who died abroad in the crusades and other wars choosing to send back their hearts to a family foundation. This raises the severely practical reason that entrails deteriorate rapidly. Hence, if a part-burial was to be far away, or after a long delay, the entrails needed to be extracted and buried shortly after death.’1

On the other hand, a small monument could simply reflect the size of the family’s budget.

Where did these stones come from?

Lichen on the surface reveals that they have spent some time outside in the past. It is possible that the stone was originally used to cover a burial outside. Coped stones like this one were a problem inside churches, because they stuck up from the pavement. However, they were more likely to have marked intramural burials of individuals who could afford a prominent position inside a church. Since the stones date from the 12th to early 13th century, and the current church dates from the 14th century, they may have laid in an earlier building, or come from another church entirely.

Thank you very much to Sally Badham, MBE, FSA, Vice President of the Church Monuments Society, for contributing her expertise to this article.

-

Sally Badham, ‘Divided in Death. The Iconography of English Heart and Entrails Monuments’, Church Monuments 34 (2019), pp. 16-76.