Scratching the surface

What is sgraffito? It all starts with the Italian word graffiare, which means to scratch. It involves the layering of coats of plaster of different colours, and then scratching off a design in the topcoat to reveal a layer of contrasting coloured plaster underneath. The process is not too dissimilar from the paint and crayon scratch drawings you might have made as a child.

Sgraffito is a form of applied decoration, and it really has quite ancient origins – though the extent of its ancient-ness is up for debate. Roman? Byzantine? Egyptian? Or ceramics from the ancient East?

But it’s certainly a technique that enjoyed widespread popularity and then disappeared for centuries, before being re-discovered and revived.

(Image below: Sgraffito to the facade of Palazzo dei Cavalieri, Pisa, 1562-64. (c) Daderot, CC BY-SA 3.0)

It enjoyed a revival in Renaissance Italy, where in the late 15th century, the designs were largely geometric – quite often imitating ashlar or rusticated stonework – to make the building look like it was built from higher quality, finer materials.

As the Renaissance progressed, and the taste for flashier, more elaborate ornamentation developed – so imagination of what could be achieved in sgraffiti stretched too, before long there were grotesques, arabesques, putti, festoons, swags and fantastical beasts swirling over building facades.

By the late 1400s sgraffiti was spreading across Europe, and gathering in popularity.

Sgraffito did reach Britain, though it’s not exactly sure how – was it Henry VIII’s importing of craftspeople from across the continent for the construction of Nonesuch Palace? (image below, Georg Hoefnagel's 1568 watercolour of the south elevation) In any case, throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, sgraffito endured on Devonian fireplaces, pottery and even the odd building.

We next really experience sgraffito in Victorian London, where it was championed by Sir Henry Cole, the first Director of the South Kensington Museum - now the Victoria & Albert Museum. Cole wanted the V&A to be an experiment, a national centre for learning and for ordinary people’s enjoyment. He wanted it to raise the standards of art education and improve the quality of industry art and design.

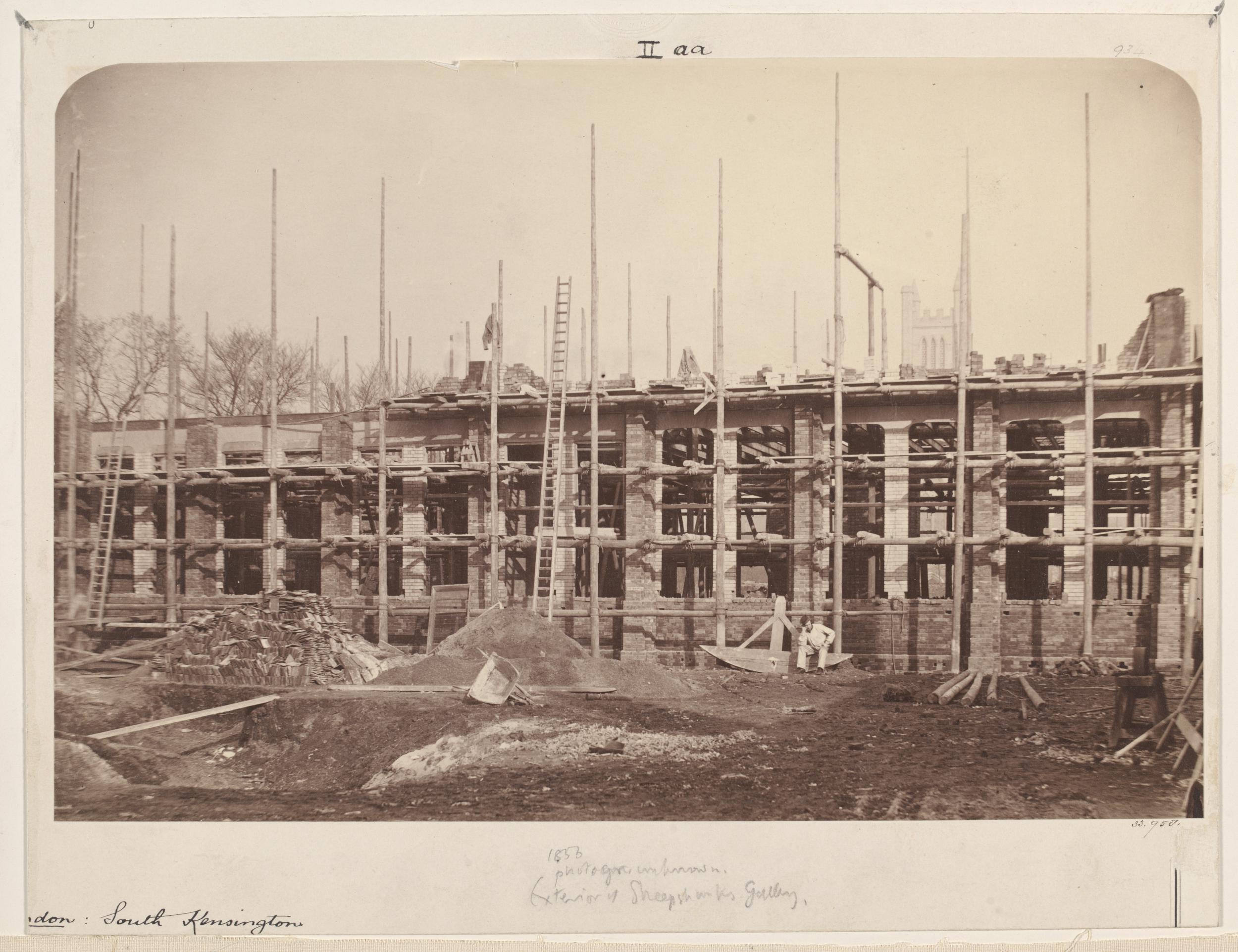

In 1856, Cole appointed Captain Francis Fowke to design a new gallery to hold the Sheepshanks collection. The exterior walls were decorated with thirteen sgraffito panels with portraits of British artists. This was the first recorded use of the sgraffito technique on buildings in England in about 300 years. (Image below of the construction of Sheepshanks Gallery, © V&A)

The panels were built over in around 1900 when the gallery was remodelled. The building is now the V&A shop.

After the Sheepshanks Gallery, further experiments in sgraffito began on the Henry Cole Wing (originally the ‘Science Rooms’). At that time the building was the tallest in South Kensington – four storeys high. Cole wanted it to be a showstopper. To achieve it, he partnered with Francis Wollaston Moody, an artist and teacher with ‘a strong Victorian certainty for aesthetics’.

Moody recruited students from the National Art Training School, and formed a team with whom he executed the entire scheme in three years (1871–3).

As sgraffito was new to them all, there was a high degree of experimentation. Moody and his students set about the task with ever-evolving mixes and methods of application as they strove to find perfect the technique. They needed to figure out how to properly prepare the surface, how to get the right level of adhesion between layers, the right set…

There’s much to say on all of this, but we’re a church charity, so we ought to focus on churches…

The earliest use of sgraffito in church decoration in the UK comes from Somerset in the early 1870s, and the work of Sir Thomas Graham Jackson. It’s St Peter’s, Hornblotton, and it incorporates terracotta and creamy-white sgraffiti in a Renaissance style. The interior scheme combines striking naturalistic patterns with free-flowing figurative depictions of prophets and Biblical scenes. (see image below)

The artists that undertook the sgraffito at Hornblotton were Francis Wormleighton and Owen Gibbons – two of Moody’s students at South Kensington. Together, they created something brand new – something entirely innovative – the first use of sgraffito as an internal decoration in a church. It was a landmark church.

Cole had intended sgraffito to be used on building exteriors – to create “urban theatre”. But really, concerns about its durability in England’s temperate climate persisted and it probably just felt a bit safer to employ it for internal decoration.

Revd W.T.A Radford championed sgraffito for internal decoration. He was a founder member of the Exeter Diocesan Architectural Society (1841) - a sister organisation to the Camden Society. In 1872, Radford presented a paper to the Society, On the Treatment of the Inner Face of a Church Wall. He argued against bare stone walls. To him, the touch of bare stone was chilling and repellent.

He rejected whitewash – the “ruthless hand of the Puritan”. On interior walls, he called for plaster. He called for colour and decoration. To him, sgraffito offered the perfect cost-effective, aesthetic solution.

In style, he opted for the Gothic Revival, a deviation from the Renaissance Revival that had been the preference. “His” schemes often had several colours – rather than the two-tone schemes of the Renaissance revival. The patterns were relatively simple, geometric and repetitive.

Radford liked the low cost, readily available materials, and felt it was a technique that could be easily undertaken by a layman– it didn’t require an artist.

The first church Radford tried out sgraffito to achieve this was All Saints, Winkleigh, Crediton with John Ford Gould as architect. (image below © @devonchurchland) Radford was obviously delighted with the result and went on to restore several more interiors in a similar way.

From the Renaissance revival to the Gothic Revival to the next interpretation of sgraffiti in the 19th century – the Arts & Crafts movement.

While Rev’d Radford brought sgraffiti to church interiors and added multiple colours to the scheme, it was George Heywood Sumner that took brought sgraffiti to a whole new dimension in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Sumner was an archaeologist and artist. And while he did lots of other things in his 87 years, for the purposes of this blog, his great legacy is sgraffito decoration in fourteen churches across England and Wales. Stylistically, Sumner’s work has very little of the Renaissance Revival, but much more of the Pre-Raphaelites. Technically, of course, it’s derived from the Renaissance Revival, but again, Sumner had his own unique take.

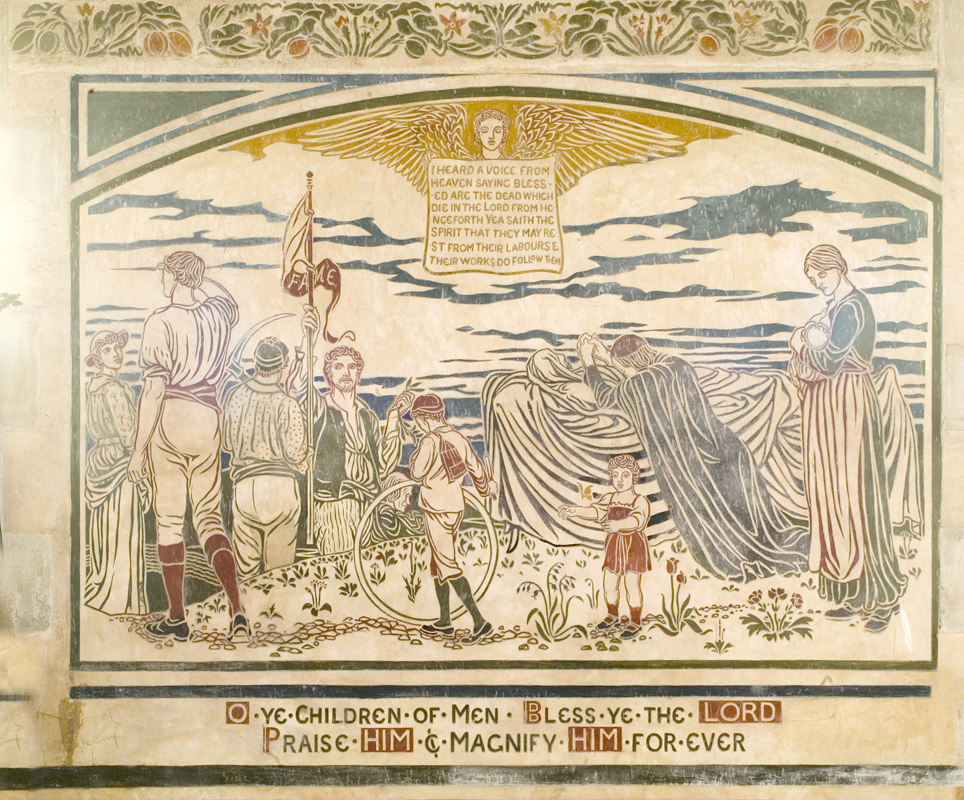

Sumner’s sgraffiti is multi-coloured, he liked to embellish it with mosaics, beads, glass fragments to enhance the work further. Sumner uses his sgraffito to tell stories – in the tradition of the medieval wall-painting. Bible stories, verses and hymns spread over Sumner’s walls.

Sumner dabbled in sgraffito – namely at his parents’ house in Winchester, before coming to Wales – to St Mary the Virgin, Llanfair Kilgeddin in particular.

The church had been rebuilt in the 1870s by John Dando Sedding. Sedding, who trained alongside William Morris and Philip Webb in G.E. Street’s offices, believed a church should be, “painted over with everything that has life and beauty – in frank and fearless naturalism, covered with men and beasts and flowers.”

But it wasn’t until 1885, following the death of Rosamond Emily Coutts, the vicar’s wife, that Sumner was summoned. Inside St Mary’s, Sumner set out the Benedicite – the hymn of praise to God's creation flowing over the walls. Everywhere you turn saints and seasons, planets and pomegranates, whales and walruses are scratched into the wall plaster.

In 'O Ye Children of Men', all the ages of life are represented, from the mother feeding her baby, to a corpse in a shroud. A young girl plays with a butterfly, lost in her childhood innocence. Next to her, a schoolboy walks towards adulthood, rolling a hoop through which we catch a glimpse of old age. Before him, workers of land and sea take a brief rest from their labours. Elsewhere sheep drink from a stream, while a farmer ploughs russet velvet field.

True to medieval tradition, Sumner included local features in his designs – for example in ‘O Ye Mountains and Hills’ on the north wall of the nave the nearby River Usk, the Sugar Loaf and Llanvihangel Gobion church tower are all included. All artistically arranged.

Sumner’s technique was as follows:

“in the studio, prepare a full-size cartoon and prick small holes along the outlines. On the site, strip the wall back to brick or stone and cover it with the coat of coarse plaster, fix the cartoon with register nails and mark the pricked design onto the plaster. Cover it with a second coat of plaster in up to five distemper colours butting up against one another. Then lay a third thin coat of light-coloured plaster to cover as much of the wall as can be worked in a day. Replace the cartoon on the register nails and mark out the design again. Later the same day, when the plaster is firm enough, cut the design out of the thin layer to reveal the ground of colours below. An assistant would prepare the walls, lay on the plaster, remove it at the end and clean up; whilst Sumner would prepare the cartoon, mark it out on the plaster, and execute the final cutting. The process was one to delight any member of the Arts and Crafts Movement; it was so earthy, so simple, so resistant to the refinements of detail; and so much depended on that last, quick and all but irreversible cut.”

We know from Sumner’s own notes that his assistant would arrive at the church at about 7am and apply the topcoat of plaster. Sumner would turn up at about 8am to mark out the design and start cutting. By midday the plaster would have set, and would be too dry to cut. Those areas would have to be chiselled off – presumably by the assistant – and cleared away. In the afternoon, area for the next day’s work would be set out, the base layers of coloured plasters applied, and allowed to dry overnight.

The top layer in Sumner’s sgraffito was thick. We know from Vasari in the 16th century and from Henry Cole’s travel in Italy in the 1850s, that traditionally the top layer was only a wash, something to scratch off. There’s no way Sumner was scratching off the cementitious topcoat at Llanfair Kilgeddin. He was cutting it – carving it. Doing something more akin to cameo cutting. So, his technique is quite original… his sgraffiti is more sculptural, 3D, it casts deeper shadows and overall has more movement and expression.

It’s astonishing to think that this church was scheduled for demolition. A report in the 1980s claimed that its structural issues were so severe that it would soon collapse. Together with the Victorian Society, the Friends embarked on a long campaign to prove otherwise, to prove that the structural issues could be overcome and more so, that this church was of such unique importance, that it had to be saved.

We eventually won, and St Mary’s came into our care in 1989. It’s now one of the most visited churches we own.

One of the proposals, was to hack out the panels of importance and stick them in some museum somewhere. This proposal flew in the face of Sumner, whose aim was to create something that belongs to its place – to the building, the landscape. He said, “ the artist must find the vitally expressive line, the essential character, movement, posture, growth and colour… and the decoration should belong to its place.”

In the early 1890s, Sumner set off for St Marys, Sunbury and Christ Church, Crookham, where he sgraffitied the chancel walls.

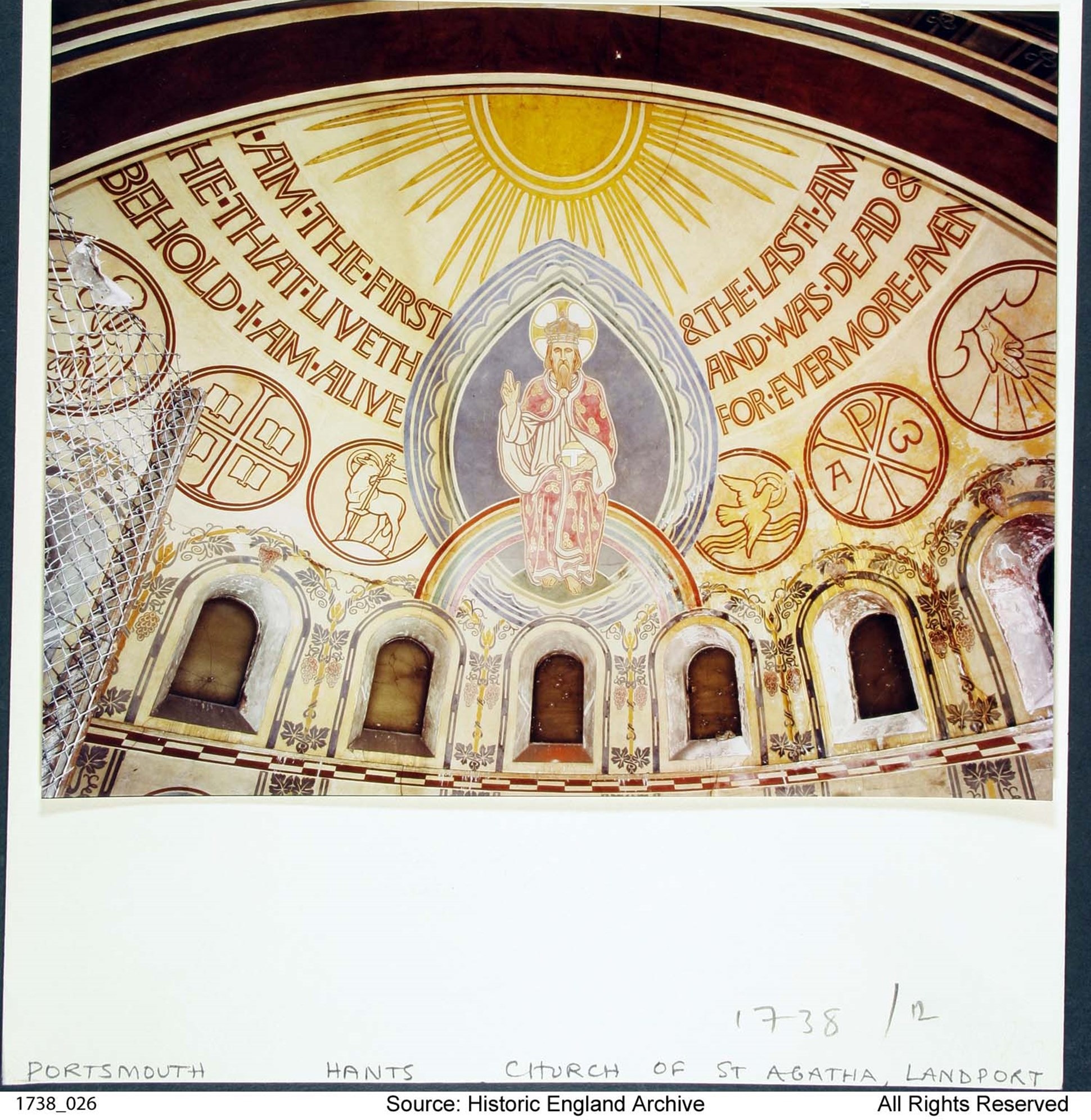

Perhaps Sumner’s most ambitious project was on a ringroad in Portsmouth in the mid-1890s and early 1900s. This was St Agatha’s, Landport.

Sumner depicts at top Christ in Majesty in the semi-dome with a representation of the radiant sun in the top of the dome and texts to the sides. Below are six large medallions including Christian symbols. Along top part of apse is a range of seven high level round-headed clerestory windows. Below is a range of Ovals with Christian symbols and below this, seven figures of Evangelists and Prophets. His work is harmonious and dignified.

Sumner came back to create this lady chapel with a Nativity scene – the manager resting on the tip of the arch. This chapel was largely demolished for road widening in 1964, and just scraps survive.

Despite being a thing of great beauty, St Agatha’s hasn’t had a great life. It was only a church for a while, then it was bought by the MOD for storing ship bits, vacant for years, then bought by the Council.

It’s interior is divided up with chicken wire, causing Nicholas Taylor to describing Christ in Majesty as an umpire in some celestial tennis court.

Heywood Sumner moved back the country in 1906, and did not create any more sgraffiti. And with that, sgraffiti in churches ended.

A pretty anti-climatic end to this article. Though I would like to give the final words to Heywood Sumner:

“Sgraffito works lacks beauty of material like glass, or mystery of surface like mosaic, or subtle weaving of tone and colour like tapestry, yet gives freer play to line than most of these. The decoration becomes an integral part of the structure it adorns. The inner surface of the actual wall changes colour in puzzling but orderly sequence, as the upper surface passes into expressive lines and spaces. It delivers it’s simple message, and then relapses into silence.”

Further reading:

- The Art of the Plasterer, Chapter 4. George Bankart;

- DBR. Sgraffito Conservation at the Henry Cole

Wing of the Victoria and Albert Museum. - Sumner, H. Sgraffito as a Method of Wall Decoration. British Art Journal, Jan 1902;

- Vasari, G. On Technique.

- The sgraffito decoration at Colaton Raleigh Church and its conservation. Devon Buildings Group newsletter.

- Cole, A. On the Art of Sgraffito Decoration, The Builder, April 26 1873.